Forestry, illegibility and illegality in Omkoi, Northwest Thailand

Versions

- 2020-09-14 (2)

- 2017-11-27 (1)

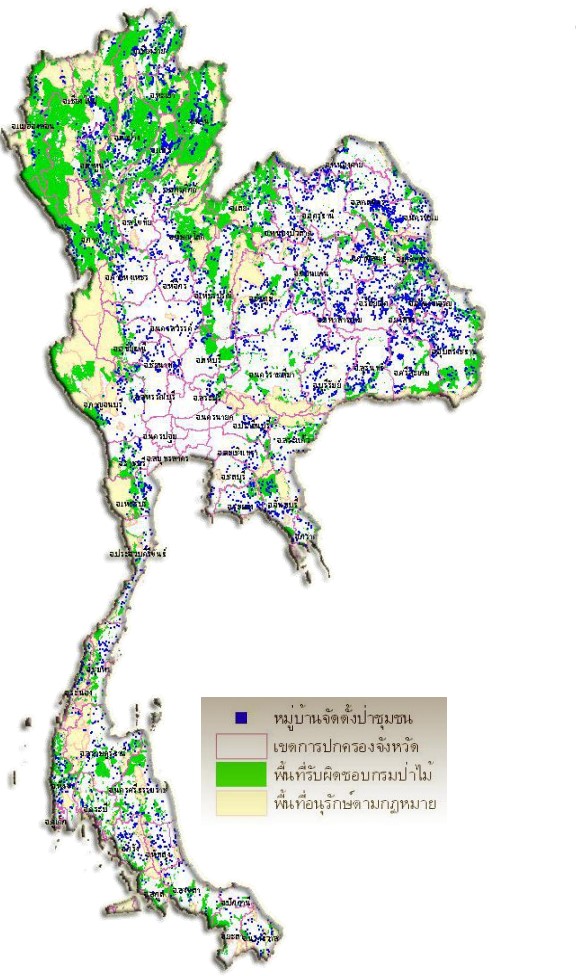

Opium poppy cultivation in Thailand fell from 12,112 hectares in 1961 to 281 ha in 2015. One outlier exists: Chiang Mai province’s remote southwestern district, Omkoi. 90% of the district is a national forest reserve where human habitation is illegal. However, an ethnic Karen population has lived there since long before the law that outlawed them was created, unconnected to the state by road, with limited or no access to health, education and other services: they cultivate the majority of Thailand’s known opium poppy, because they have little other choice. They increasingly rely on cash-based markets, their lack of citizenship precludes them from land tenure which might incentivize them to grow alternate crops, and their statelessness precludes them from services and protections. Nor is the Thai state the singular Leviathan that states are often assumed to be; it is a collection of networks with divergent interests, of whom one of the most powerful, the Royal Forestry Department, has purposely made Omkoi’s population illegible to the state, and has consistently blocked the attempts of other state actors to complexify this state space beyond the simplicity of its forest. These factors make short-term, high-yield, high value, imperishable opium the most logical economic choice for poor Karen farmers residing in this “non-state” space.

Anderson, B.O.G. (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

Anderson, B. (2015). Papua’s Insecurity: State Failure in the Indonesian Periphery. East-West Center Policy Studies 73. Honolulu: EWC.

Anderson, B. (2017). People, Land and Poppy: the Political Ecology of Opium and the Historical Impact of Alternative Development in Northwest Thailand. Forest and Society, 1(1), 48-59. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.24259/fs.v1i1.1495

Anderson, B., Tan, T.Y., Woodcock, S., and Jongruck, P. (2016). Thailand’s Last Opium War: Governance and Illegality in a Highland Periphery. National University of Singapore Governance Study Project.

Asia Indigenous People’s Alliance. (2012). Drivers of Deforestation? Facts to be considered regarding the impact of shifting cultivation in Asia. AIPP. http://ccmin.aippnet.org/attachments/article/956/Driver_%20of_Deforestation.pdf, last accessed June 29 2016.

Bruun., ilde B., Andreas de N., Deborah, L., & Alan D. Z. (2009). Environmental Consequences of the Demise in Swidden Cultivation in Southeast Asia: Carbon Storage and Soil Quality. Human Ecology 37; ASB-Indonesia Report Number 4, Bogor.

Cheesman, N. (2002). Seeing “Karen” in the Union of Myanmar. Asian Ethnicity 3(2), 199-220.

Delang., C. O. (ed). (2003). Living at the Edge of Thai Society: The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand. London: Routledge.

Erni, C. (2009). Shifting the Blame? Southeast Asia’s Indigenous Peoples and Shifting Cultivation in the Age of Climate Change. Paper presented at Adivasi/ST Communities in India: Development and Change”, Delhi, August 27-29.

Forsyth., Tim., & Andrew, W. (2008). Forest Guardians, Forest Destroyers: The Politics of Environmental Knowledge in Northern Thailand. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Hanks., Jane, R., & Lucien, H. (2001). Tribes of the North Thailand Frontier.

Monograph 51, Yale Southeast Asia Studies.

Hinton, P. (1983). Why the Karen do not Grow Opium: Competition and Contradiction in the Highlands of North Thailand. Ethnology 22(1): 1-16.

Irrawaddy. (2016). KNU Signs Forestry Memorandum with WWF. November 9. http://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/knu-signs-forestry-memorandum-with-wwf.html, last accessed January 4, 2017.

Jongruck, P. (2012). Network Governance through Resource Dependence Theory: a Case Study of Illicit Drug Policy in Thailand. PhD dissertation, University of Manchester (UK).

Jongruck, P. (2015). “From Bureaucracy to (Mandated) Network: A Changing Approach to Opium Eradication in Northern Thailand”. 15th International Research Society for Public Management Conference, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom, March 30 – April 1.

Laungaramsri, P. (2005). Swidden agriculture in Thailand. Myths, realities and challenges. Indigenous A airs 2/05. Copenhagen: IWGIA.

Leach, E. (1954). Political Systems of Highland Burma: a Study of Kachin Social Structure. London: Anthlone Press.

Office of the Narcotics Control Board. 1995-2015. Opium Cultivation and Eradication Reports for Thailand.

Ongprasert, P. (2011). Forest Management in Thailand. Participants Reports on Forest Resources Management: 151.

Phromlah, W. (2013). A Systems Perspective on Forest Governance Failure in Thailand. GSTF International Journal of Law and Social Sciences 3/1, October.

Puginier, O. (2003). The Karen in Transition from Shifting Cultivation to Permanent Farming- Testing Tools for Participatory Land Use Planning at Local Level, in Delang, Claudio O. (ed). 2003. Living at the Edge of Thai Society: The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand. London: Routledge, 183-210.

Rashid, A. (2000). Taliban: Militant Islam, Oil and Fundamentalism in Central Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Renard, R. D. (2001). Opium Reduction in Thailand, 1970-2000. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books.

Scott, J. C. (1998). Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Scott, J. C. (2009). The Art of Not Being Governed: an Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New York: Yale University Press.

Smith, M. (1991). Burma: Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London: Zed Press.

Tilly, C. (1985). War Making and State Making as Organized Crime, in Evans, Peter, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol. Eds. Bringing the State Back In. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tilly, C. (1990). Coercion, Capital and European States, AD 990 – 1992. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

[UNESCO] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2010. Highland Household Survey. Last assessed 7 Apr 2016. http://www.unescobkk.org/culture/diversity/livelihood/surveys/impacts-of-legal-status-on-access-to-education/

[UNODC] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2007-2014. Southeast Asia Opium Surveys.

[UNODC] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2014. Last accessed May 2016. https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific//cbtx/cbtx_brief_EN.pdf

Winichakul, S. (1994). Siam Mapped: a History of the Geo-Body of a Nation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Copyright (c) 2019 Forest and Society

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This is an open access journal which means that all contents is freely available without charge to the user or his/her institution. Users are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. This is in accordance with the BOAI definition of open access.

Submission of an article implies that the work described has not been published previously (except in the form of an abstract or as part of a published lecture or academic thesis), that it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, that its publication is approved by all authors and tacitly or explicitly by the responsible authorities where the work was carried out, and that, if accepted, will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or in any other language, without the written consent of the Publisher. An article based on a section from a completed graduate dissertation may be published in Forest and Society, but only if this is allowed by author's(s') university rules. The Editors reserve the right to edit or otherwise alter all contributions, but authors will receive proofs for approval before publication.

Forest and Society operates a CC-BY 4.0 © license for journal papers. Copyright remains with the author, but Forest and Society is licensed to publish the paper, and the author agrees to make the article available with the CC-BY 4.0 license. Reproduction as another journal article in whole or in part would be plagiarism. Forest and Society reserves all rights except those granted in this copyright notice